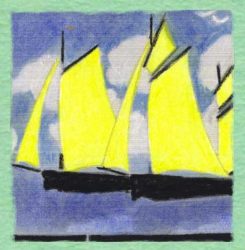

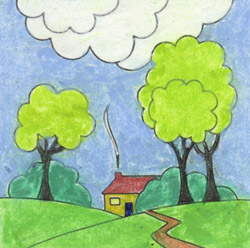

These residents of Poplar had little money to spare

But they had big dreams. That now the war was over their poverty-stricken lives would change forever and the East End of London would, indeed, become a land fit for heroes. That promise echoes to the sound of hollow laughter almost 100 years later, but they weren’t to know what was around the corner and they – for the most part anyway – believed what their politicians told them.

The area around the London docks had mixed fortunes during the 1914-18 conflict. For the men working in reserved occupations such as the stevedores, coal whippers, lightermen and dockside porters, life carried on much as normal – except with less to eat and more empty ships’ holds as food blockades bit – and there were fewer devastated East End families than in other areas of Britain. But the docks were a far from safe place to be. On June 13th 1917 a bomb was dropped on Upper North Street School where 64 children were being taught. Eighteen were killed, fifteen of them aged 5. It wasn’t only the older generations who knew, firsthand, the horrors of war.

Josephine Tey wrote in A Shilling for Candles: We came through the Great War well, but perhaps the effort was too great. It left us – epileptic. Surviving, in one sense, was only the beginning. Front-line reportage influences our responses to war even as it happens whereas, instead of information, Britain in the 1920s was flooded with a sort of collective amnesia which worked to deny on-going suffering. Wilfred Owen didn’t write his poems of remembrance for us, but to awaken his contemporaries. If the past teaches us anything at all, it is that uncomfortable truths can’t be made to go away.

Postcard by kind permission of Philip Mernick