London September 1927

The play of motives passes through all kinds of vicissitudes as the alternative courses of action and their consequences are more fully apprehended in relation to the self.

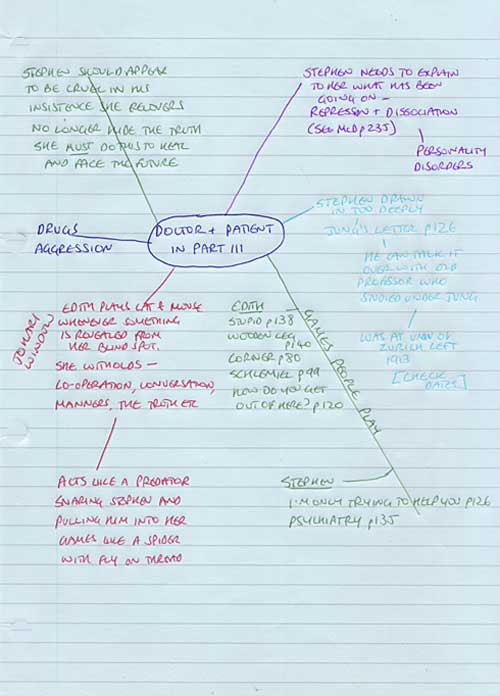

The quotation from Stout that marks the middle of the novel could be Stephen’s summation of what he hopes to gain by confronting Edith with a version of the truth. Except, whose truth is it? Here is a glimpse into my sheaf of work in progress notes on their relationship:

- They are more alike in their fears and uncertainties than either wants to admit.

- Help and humiliation: can you have one without the other? Both respond as if they have been humiliated, even when it is self-inflicted punishment.

- Her knowledge of psychiatry means Stephen can get Edith to share in her therapy. What he doesn’t realise is that she can also subvert it.

- Stephen knows what will happen to Edith if she refuses to accept and adapt. But his cowardice lets them both down. He is unable to live up to his ideals but expects others to.

- From McDougall: An Outline of Abnormal Psychology (1926): ‘A peculiar way of making oneself important is finding joy in misery; one always sees to it that one is the victim of injustice, usually only in little things . . .’

- Dr Maynard is a great one for theories. Trouble is that all his patients have their own agenda and he doesn’t always take that into account.

Explore more of my mind-maps: