Walls of Silence is the novel that wouldn’t let me alone. I returned to it time and again over a period of twelve years, each revisit seeing me bolder and more experimental as my skills and confidence grew. After a mercifully brief flirtation with the title ‘The Hand-turned Dobby’, I hijacked ‘Walls of Silence’ from a novel I’d written early on in my apprenticeship about a motorcycle stunt show in a travelling fair.

The themes of madness, social isolation, shell-shock, and repression have been consistent throughout this book’s long gestation but I wasn’t a good enough writer in the early days to handle such weighty material; I lacked the skill to construct a plot suitable for exploring the psychological makeup of a damaged mind. It was a murder mystery of sorts when Val McDermid read the first line (I wrote the opening paragraph whilst on an Arvon Crime Writing course) but now I think of it as a psychosocial* novel in which the violence perpetrated is as much institutional as it is defining in its vengefulness.

As the wall of death drome and fairgrounds of the original story disappeared on the horizon, I had to change my research focus. The file on shell-shock was expanded to include the attempts at treatment (primarily in order to get the troops well enough to send them back into war) and this branched out into asylums, the assessment of mental health and psychiatric disorders, and what (if anything) constituted rehabilitation.

The hardest thing of all when writing a historical novel is to assume the viewpoints of the time and to close down the vistas of knowledge from later years. The assiduous author uses research to direct the limits and boundaries of a given time as well as to provide opportunities for the reader to ponder the ironies thrown up by hindsight. It requires a light touch to incorporate all the benefits good research practice can bring but, luckily, one of the things you acquire as you mature as a writer is sleight of hand.

Edith Potter, the main character and victim of Walls of Silence, has haunted me since she emerged from my subconscious over a decade ago and I so hope I have, at last, been able to do her story justice.

[* of or involving the influence of social factors or human interactive behaviour. OED ]

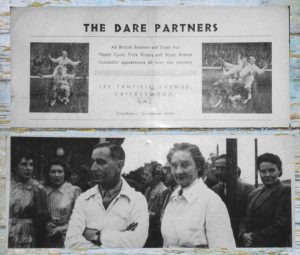

Now, there is a story in its own right about the image on this page. I was at the Beaulieu motorbike show for some research on old machines when I noticed a little old lady (literally!) being interviewed in the main ring. There were fairly patronising questions about when, aged 80, she’d ridden around Brands Hatch but then she seemed to get bored and digressed onto stunt riding. She was one half of the Dare Partners (with her brother) and in the 1930’s drew crowds at Crystal Palace for their shows. Jessie confessed that when she first started she was green enough to think she could copy the trick of riding through a sheet of plate glass, unaware the other acts used sugar-glass. So she used the real thing – a huge sheet of Pilkington’s. I got to know her and on a visit to her house she unearthed a lot of her memorabilia, included the leather helmet she’d worn for that first glass stunt. It had an enormous rent on one side where a shard had dropped like a dagger and narrowly avoided killing her. Jessie Ennis (Hole as was before she married Bill). Speedway rider, hill-climber (she had her mother in the sidecar as ballast!), WW2 ambulance driver (she volunteered because she loved fast driving), and general daredevil. When I get around to it I will dig out the transcripts of my interviews and write a whole piece about her. (Meanwhile, you can find her in a starring role on the Wey Valley Advanced Motorcyclists website). She was an inspiration. And the person at the heart of the motorbike stunt riding in my apprentice-piece wall of death novel. Perhaps I’ll resurrect and rewrite that too one day . . .

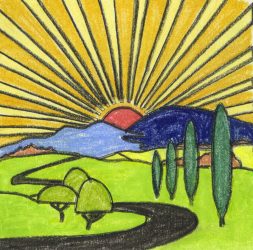

And, just because I can’t resist it, here is the picture of the lovely Jessie I have stuck in the front of my research notes on her. It was taken in 1928. So, so much more than that pretty face: