Much of my research is around language. In fact, all my writing starts and finishes with the words I choose to use. In historical fiction, if you can capture what was said in the street and the pubs – as well as the phrases used in contemporary novels and newspapers – then a lot of the work of creating the atmosphere of the era is done. We communicate (especially orally) via a shared understanding of what certain words mean in and out of certain contexts – for example, text meant something different now than it did when I was a child, as did gay and neat and massive and vintage.

The BBC has a long-running radio programme called Desert Island Discs where guests are allowed to select a book to keep them company until they are rescued (they already have the Complete Works of Shakespeare and an appropriate religious or philosophical work). When it’s my turn to be a castaway, I shall request Eric Partridge’s A Dictionary of Slang and Unconventional English. It would keep me amused and curious and stimulated in equal measure. Perhaps I could even use it to try teaching the parrots to answer me back.

Cant is the language of the underworld. Partridge describes it as ‘the vocabularies of crooks, criminals, racketeers, beggars and tramps, convicts, the commercial underworld, the drug traffic, the white slave traffic, and spivs’. And of this writer.

When I start to research a new novel, I reach for one of my many vocab books (like the ones I used for French and Latin at school) and head-up a new section for the unfamiliar, colourful, obscure, delightfully time-bound, or words I want my characters to say; as well as those used for things which were common at the time but have since disappeared, and the words that now mean something different.

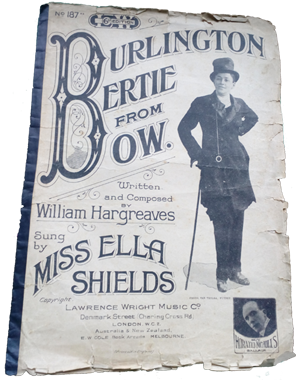

The vocabulary of those living and working in London’s Poplar and Limehouse in the 1920s was rich and varied, with some words so local to the trades and communities of the area that someone from the other side of the river would have difficulty understanding them. To give you a flavour of the sources that went into the mix:

- immigrant communities such as Chinese, Irish, Jewish, French, Scandinavian, Indian, Malaysian

- shipbuilding, chandlers, associated dockside trades

- manufacturing industries

- sailors and the home countries of the ships

- groups and gangs wishing to converse without being understood.

In 1929 George Orwell included a chapter on London slang in Down and Out in Paris and London (published 1933).

Why not have a go at working out what the cant below means – even better, bring to back to life by dropping the words into casual conversation (as Orwell would’ve done) for a bit of 1920’s East End fun.

- A judy.

- Shackles.

- To skipper.

- A drop.

- A clodhopper.

- Hard-up.

- To knock off.

- A flattie.

- A toby.

- Fuhkum.

- A peter.

The answers Orwell gave can be found in the post Slang and cant decoded.